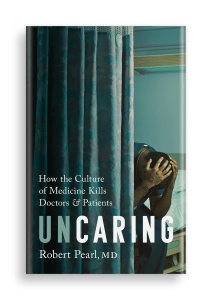

The following is an exclusive excerpt from my newest book “Uncaring: How the Culture of Medicine Kills Doctors & Patients,” which is available this holiday season in audio book, ebook and hardcover. All profits from “Uncaring” and from my previous book “Mistreated” go to Doctors Without Borders.

This is a story about my Aunt Ruthie, who lived to be 99 years and 9 months old. One day while visiting her apartment in Manhattan, I made a startling discovery, one that could have cut her life short by several years. The lesson of her story involves two of medicine’s most urgent (yet fixable) failures …

starting on page 161 …

All her life, my aunt Ruthie was remarkably energetic and resilient. When she lost her hearing in her seventies, she taught herself lip-reading. Even well into her nineties, she stayed spry and mentally sharp. She was, in every way, her mother’s daughter: proud and determined. Her mom, my grandmother, was responsible for the operations of a large network of parking garages in New York—a role she began in her eighties. In her seventies, my grandmother helped publish and distribute what she called “movie star magazines,” forerunners to People and Us Weekly.

With her mom as her role model, Ruthie refused to let advancing age slow her down or let anyone tell her what to do. Living in a retirement facility was out of the question. Instead she kept her apartment in Lower Manhattan, spending her days exploring the South Street Seaport and people-watching along the waterfront. On nice days, she’d hit the pavement with her walker, bopping from one park bench to the next until around noon, when she’d find a cozy or trendy new place to dine. Whenever I was in New York, she’d take me to her favorite lunch spots, always insisting it was her treat.

One beautiful spring day, with blue skies above and a light breeze on our faces, Ruthie and I popped into a charming deli, where we dined on matzo ball soup and pastrami sandwiches. Afterward, I walked her back to her apartment and asked to use the restroom. On the bathroom floor was a trash bag filled with dozens and dozens of plastic pill bottles. On my way out, I asked who’d prescribed all those medications. From memory, my aunt provided the names of six or seven different physicians.

Looking closer at the bottles, I realized many of the drugs had been initially prescribed years ago. I asked if she still needed them. She didn’t know for sure, but she assumed she did since her doctors kept renewing them.

I urged my aunt to make an appointment with a physician who could review, evaluate, and coordinate her medical care. She agreed and scheduled a visit with a gerontologist I recommended in the Village. A few months later, when I was back in Manhattan, we met again for a nice walk and some lunch, this time at a cute little bistro with a flowery, fenced-in courtyard area. Her treat, as always. After we caught up on life and family news, I was eager to hear what the gerontologist told her.

“He said I could keep taking the medications if I wanted to, but only one of them makes much of a difference at my age,” she replied.

“What did you decide to do?” I asked.

“I went to the pharmacy and dumped the whole bag in a disposable container,” she said with sparkling laughter. She was relieved to have reclaimed all that extra space on her bathroom floor.

Physician’s note: The advice Ruthie received would not have been appropriate for a patient with serious medical issues, like heart failure or asthma. But it was the right thing for my aunt, and it was long overdue. A few weeks after she dumped the pills, she noticed most of the distressing side effects from her old medications were gone.

My aunt lived another eight years, passing away a few months shy of her one hundredth birthday. Looking back, Aunt Ruthie was the perfect patient: she always kept up with her appointments, followed physicians’ recommendations, and took all medications as prescribed. And as a result of being the ideal patient, she wound up with a trash bag filled with medications, nearly all of which were unnecessary.

Each of her physicians was well trained, competent, and highly respected. Yet the care my aunt received was fragmented, uncoordinated, and potentially dangerous. This discontinuity in American medicine is ubiquitous and cultural, demonstrating how the beliefs and norms of doctors don’t always align with what’s best for patients.

Physicians approach the needs of patients using a two-part recipe: one part science and one part culture. The result is a system of care that’s technically excellent, but imprecise and impersonalized. To understand why, it’s essential to see patients and their problems the way doctors do. Physicians know that, biologically, patients are more alike than different. Despite the billions of people on this planet, all human DNA is 99.5 percent identical. This means that regardless of one’s race, gender, or place of origin, a person’s medical needs and treatments can almost always be determined reflexively based on laboratory results. If a biometric number is too high, the doctor’s job is to lower it. Too low, the doctor raises it. Once a patient’s lab results are within a normal range, doctors keep prescribing whatever medications got them there and will help keep them there. Success is measured by whether follow-up studies are normal, not whether the care provided makes a person happier or more fulfilled. In no medical textbook will a doctor in training receive the following advice: If a ninety-year-old woman’s greatest pleasure is walking along the waterfront, then do not prescribe a medication that causes lightheadedness and puts her at risk of falling, even if it offers a small chance of extending her life by a few months.

Doctors are trained to make “the right medical decision,” not to spend time finding out what matters to a patient so that, together, they can select the right option for that particular individual. This approach exists partly because finding out what matters most to a patient is difficult. Filling in the blanks of people’s lives—discovering their unique desires, expectations, and preferences—takes a lot of time and evaluation. And time, for doctors, is more limited now than ever. As a result, physicians embrace a one-size-fits-all approach that can effectively treat disease but often ignores a more humanistic truth: what’s best for one patient may not be optimal for another, even if they do share similar DNA.

This view that all patients are identical leads to another cultural misconception: If all doctors focus on their own specialty and do their jobs correctly, there’s rarely a need to touch base, collaborate, or look over one another’s shoulders. This belief is widespread and the reason doctors fail to coordinate care. They see their jobs as specialty specific. If you are a cardiologist, only the heart matters. If you are a gastroenterologist, you focus solely on the food passage and the associated organs. If you are a hematologist, it’s all about the blood.

Renowned surgeon and author Atul Gawande summarized it well in the New Yorker: “The public’s experience is that we have amazing clinicians and technologies but little consistent sense that they come together to provide an actual system of care, from start to finish, for people. We train, hire, and pay doctors to be cowboys. But it’s pit crews people need.”

Indeed, physician culture, like American culture, worships heroes and superstars. The heroes are those who focus on, and master the treatment of, one organ (like the heart or kidneys) or one specific disease (cancer or arthritis). Physicians undervalue the generalist, the doctor who connects all the pieces. As a result, rarely does any one doctor take responsibility for the totality of a person’s medical care.

Within physician culture, the best medical care results when each specialist corrects every abnormality identified within their narrow specialty. The overriding assumption is that all the pieces will somehow fit together. It is a poor assumption.